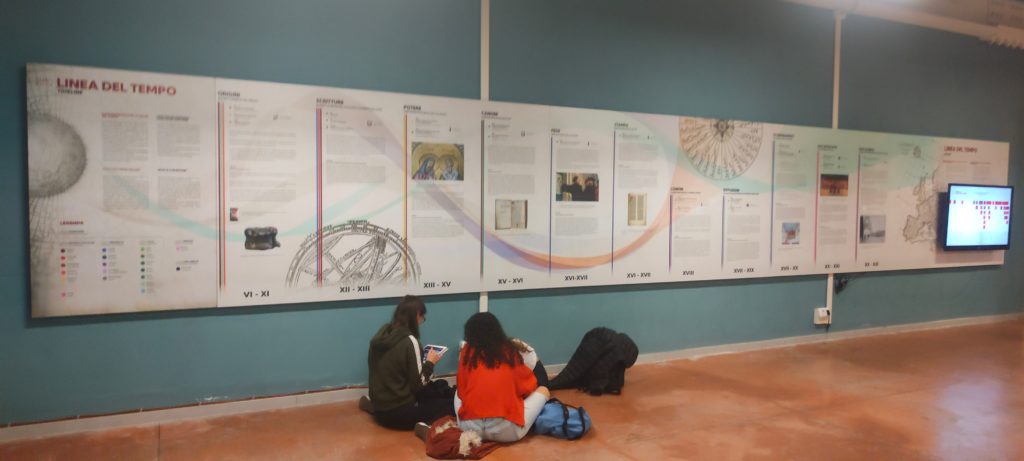

HOW CAN WE REPRESENT LANGUAGES OVER TIME?

Timelines are typically used in order to study the historical trajectories of individual languages by developing a framework for their evolution. Rarely proceeding along a straight line according to a predictable trajectory, languages are human heritage which live and belong to different histories depending on one’s point of view.

Displayed here are eleven themes (or points of view) to narrate a history of European languages seen through their different MILESTONES.

Languages never begin or end, but rather they transform, merging and separating from each other on the legs of the people who speak them as they conquer lands, marry, and migrate in search of work, sustenance or adventure. At some point in history, a dominant social group will decide to use its commonly-spoken language as an identifier of the larger community. It is at such moments, for example that a descendant of Latin becomes French (or Italian, or Occitan, or Spanish), or West Saxon becomes English, while all other tongues spoken in the same territories come to be known as dialects.

When does a spoken language become a literary language?

No one learns to write by speaking. Unlike spoken languages, written literary languages possess names and may be counted. Just as the territories of the ancient Roman Empire adopted Latin as their language of culture and political discourse yet continued to use their local languages for most exchanges, so too does medieval Europe embrace Latin as the primary language of writing, only a few of the modern vernaculars graduating to writing. We consider to be MILESTONES of the language the first written attestations of that language, and the most historically or culturally significant literary productions such as the great Anglo-Saxon epic, Beowulf, the earliest Old French Romance the Chanson de Roland, and the Provençal love poetry brought to Sicily, perhaps on the legs of the German Minnesänger, and finally to Tuscany where the form is diffused throughout Europe by Petrarch. A handful of literary languages mark the beginning of modern literature in the whole continent.

Does every centre of power have its own language?

Just as Latin anchors the Church of Rome, in the ninth century the brothers Cyril and Methodius of Thessaloniki, known as the Apostles of the Slavic peoples, codify Old Church Slavonic to perform the same function for the Eastern Church.

The diversification of the centres of power in the European High Middle Ages empowers languages associated with the royal courts: in 1274 Alfonso X declares Castilian to be the language of his domain in Spain, in 1279 Portuguese becomes the principal language of the Royal Chancellery of Lisbon, and in 1346, Charles IV is crowned Emperor and founds the Universitas Carolina which plays a central role in Czech identity and language. In 1362, English is used officially for the first time in the English Parliament, while in Italy throughout the 19th c. Italian is used in official functions alongside French

How are grammars born?

Starting from the 15th century Europeans, convinced that some modern languages–typically supported by political centres–needed fixed rules of spelling, grammar and rhetorical form in order to bolster their prestige, begin writing grammars of modern languages. Leon Battista Alberti drafts the first around 1435 in order to demonstrate that Tuscan is a worthy heir to Latin and not just a language of the marketplace. The period, especially after the emergence of printing (from 1450) also witness the birth of the Russian epic (Slovo o polku Igoreve, 1550), the publication of the first book in modern Greek (Bergadis’ Apokopos, Venice, 1509), the first Czech dictionary and grammar (1511, 1533), the first Hungarian grammar (1539), and treatises on the rhetoric of modern languages such as Pietro Bembo’s Prose della Volgar Lingua (1525) and Joachim du Bellay’s Deffence et illustration de la langue françoise (1539). At the end of the sixteenth century the first grammars of Slovene, Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian arrive.

What language does my faith speak?

Cuius regio eius religio (the king’s religion is that of his subjects) belongs to the period of the religious wars in Europe. In 1522, an act of translation enflames the Protestant Reformation: Martin Luther publishes his epoch-making German translation of the New Testament which simultaneously destroys the linguistic unity of the Western Church while stimulating and promoting linguistic unity among German peoples. Translations of the sacred text in spoken languages, previously confined to often prohibited manuscripts, are printed in authorized versions and erupt like wildfires across Europe, from the Hussite Bible translated into Hungarian in 1466, to the Polish (1553), Ukrainian (1556), Slovene (1557), Czech (1579), and Rumanian (1582) translations, soon followed by the King James Bible in English of 1611. Cemented by faith and religious identity, these historical turning points are of great symbolic significance for the perception of language within nations.

An unnoticed revolution?

Dating to Late Antiquity, the book form we still use today represents and transmits knowledge preserved by institutions such as the Roman Church and courts. The printing press upsets this mode of safeguarding memory by reducing the cost of books, and exponentially augmenting their circulation, notably within social groups traditionally excluded from reading who could now buy books in languages they know.

The first printed books in European languages offer a singular image of Early Modern European culture: in Germany it is a collection of short stories (Bamberg, 1461), in Venice it is Petrarch’s Canzoniere (1470), and in Lyon it is Jacopo di Voragine’s famous collection of saints’ lives, the La légende dorée (1476). The first English language printed book, a translation of the Historyes of Troye, a text wildly popular throughout Europe, was printed in Bruges in 1473. In Portugal, the Hebrew Torah is the first book published (1487), in Poland, stories of the Passion (1508) and in Romania, the Lutheran Catechism (1544).

Does naming a language give it boundaries?

Nations, states and languages are often perceived as one and the same thing. We normally date the birth of the English, French, Portuguese and Spanish nations and languages to the Middle Ages, and of Italian with Dante and his ideas about language. But what do today’s nations and languages bearing the same name share with their medieval selves? The territories of Central Europe, devoid of natural confines and barriers like mountains and seas, have witnessed centuries of political and social tensions related to belonging and self-determination. Similarly, Serbia and Greece preserved their identities – linguistic and otherwise – despite 400 years of Ottoman rule. The Austro-Hungarian Empire united peoples and separated religions, and the tragic after-effects are still felt today. Languages are the steel web that weaves the weft of our belonging–an instrument of dialogue and communication–yet also a major cause of distance, impasse and separation.

‘You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you

For learning me your language’

(Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act I, Scene 2.437-9)

so responds an angry Caliban to Prospero who treats him as a savage.

Commercial interests and imperial ambitions project European nations beyond their borders, westwards, to Ireland (1541), and North America (1608), and eastwards to Indonesia (1619), the Indian subcontinent (1757), and eventually Australia and New Zealand (1768), exporting English, French and Dutch across the globe. Spanish and Portuguese permeate Africa, South America and the Far East from 1493. Large and small powers loot and colonise Africa, displacing populations through slave trade, killing communities and languages, and blanketing the entire Modern period in shame. The British Empire reaches its greatest expansion in 1920. English is still widely used in the territories of the Commonwealth, while American English dominates anglophone contemporary culture.

Whose heritage is protected by academies and legislation?

It represents an important coming of age when languages and science receive official status in rule-making national organisations. Academies begin honouring and defending languages in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including the Accademia della Crusca (1582-83), Die Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft (1617), the Académie Francaise (1635) and the Real Academia Espanola (1731). Scientific academies, as well as societies intended to support national languages and cultures abroad follow suit, including the Accademia degli Lincei (1603), the academies of Slovenia (1693), Ukraine (1694), and Russia (1710), and the Alliance Française (1883), Dante Alighieri (1889), British Council (1934), and Goethe Institute (1951).

The rights of specific language speakers receive important legislation such as the use of Demotic Greek in schools in 1976. In 1999, UNESCO institutes the International Mother Language Day and Italy enacts laws to protect the numerous linguistic communities present in its territory. In 2014, the Norwegian Parliament votes that both Nynorsk and Bokmål become official languages of the state.

To whom does a language belong?

Language is created by the poor and appropriated by the rich to mock those who do not speak like they do, wrote Don Milani’s students in Lettera a una Professoressa (1967), an essay which raises the issue of language as an instrument of power and social exclusion. Since then, Europe has been holding open discussions about the discriminatory uses of language with respect to immigrants, women, gay, and more recently, transgender people.

Even our mode of naming languages Italian, English, German, Russian, French, Latin, Serbian, or Croatian gives the false impression of unity and immobility–a platonic ideal for which we are sometimes even willing to kill or die. People do not speak with a single voice nor do they speak ‘correctly’ by some objective standard. The paradigm of categorising language into standard/popular /substandard/native/foreign/majority/minority languages is now rightly subjected to harsh criticism.

By reaching more people, do we enrich language?

Periodicals, telephone, radio, television, and eventually internet and social media all expand the boundaries of language, increasing the range of some tongues and reducing the voice of most others. The first periodical in English was printed in Amsterdam (1620); other periodicals followed, e.g. Paris (1631), Lisbon (1641), Krakow (1661), Moscow (1702), Pest (1780), Bucharest (1829) and Zagreb (1835). The Eiffel Tower emitted the first radio transmission in 1921, soon followed by broadcasts from the BBC (1922), and television (London, 1925), though the latter would take until the 1950s to become widely diffused in Europe. In 1990, Tim Berners Lee creates the first website, while the following decades generate fast-paced experimentation with social networking, culminating in the launching of Facebook (2004), Twitter (2006), WhatsApp (2009), and TikTok (2017).

CONTRIBUTE A LANGUAGE

If you would like to propose new languages, we accept contributions in Excel format with images in JPEG format.

Download the template.