Inscriptions

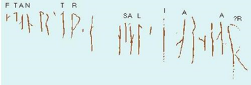

(Þ) [HAL]FTAN [. . .]

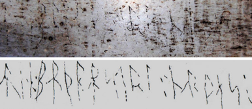

ARINBÁRÞR REIST RÚNAR ÞASI

(Þ) [HAL]FTAN [. . .]

ARINBÁRÞR REIST RÚNAR ÞASI

Description

At some time in the late 9th to 11th c., a Nordic man, probably from present-day Sweden, etched his name [link to personal names] in runic script on a marble parapet high up in the 6th c. church building of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, capital of Byzantium. Today, only some of the runic letter-forms can be read, but this is enough to identify the name Halftan and to infer that the remaining forms spelt out the Old Norse equivalent of ‘carved these runes.’ Another, later runic graffito, in the same gallery of the church, reads ‘aribárÞr cut these runes;’ it is found among other, later medieval Cyrillic and Greek graffiti on the same window ledge. These two inscriptions are good examples of the age-old practice of scratching one’s name onto a surface in a public place, and thus immortalizing [link to memory] one’s presence and one’s otherwise long-silenced voice. Traces of departed Scandinavian people and their voices are provided by Old Norse runic graffiti of this nature, and extend from the North-Western territories of Newfoundland and Greenland to where the South-Eastern part of the European land-mass meets Asia, in Constantinople.

Speakers of Old Norse (ON) from Scandinavia came to Byzantium as traders, pilgrims, and also as raiders and warriors. They were the same peoples as the Norsemen in longboats, the vikingr or Vikings (perhaps meaning ‘one who has travelled in a group’) who had been trading, raiding and settling along the Western European seaboard since the 8th c. Those who travelled south and east along the Dniepr-Baltic route down through the steppes through the were known as the Rhos, Ros, or Rus (the name derives from róðr and róðrsmennn , “to row” and “oarsman”), the Finns calling them Ruotsi and the Arab chroniclers naming them ar-Rus. After agreeing to form a fighting unit for the Byzantines, they were also known as Varangians (from ON væringr, from várr or værr, “pledge”). As the runic script and their Scandinavian names indicate, the Rus inscribed the Hagia Sophia runes. Voices of 9th to 12th c. Constantinople By the 9th c. even Byzantine officials and educated elites no longer spoke Latin, which they used only as a learned language in some writings; the main language was a medieval, demotic Greek (the name Hagia Sophia , or Ἁγία Σοφία, is Greek for the Latin Sancta Sophia, which means ‘Holy Wisdom’). Outside of the palace walls this language was joined by the voices of merchants, traders and visitors from all over the world. In the linguistic melting-pot [link to: languages in contact] of Constantinople, local varieties of Greek would be heard alongside Arabic, Persian, Turkic, Slavic and many more languages: the Jewish merchants alone used Arabic, Persian, Latin, Frankish, Andalusian, Georgian and Slavic. It is most likely that Old Norse would have been spoken only among themselves by the Rus, although after 1066 they might have been able to communicate in their own language with Anglo-Saxon arrivals, people who had fled [link: to migrants, exiles] from the Norman invaders of their country. Some of these Old English speaking exiles joined the Varangian Guard. Their language resembled Old Norse, which they might have been familiar with from speakers in the old Danelaw parts of England. A longer runic graffito thought to have been inscribed by the Rus in Byzantium within this period is elaborately etched onto the shoulder of a marble lion that used to stand in Piraeus. The Piraeus lion is now at the Arsenale in Venice.

Storage

Both inscriptions have some badly worn parts, and the Halfdan inscription is only partially readable

Bibliography

Wladyslaw Duczko, Viking Rus. Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe, Leiden, Brill, 2004

Links

Transcription author: Svärdström (Halfdan transcription); Melnikova (AribárÞr transcription)

Card author: Margaret J-M Sonmez

Publication Date: 2021-09-30

Halfdan and AribárÞr Graffiti

Trace type: graffiti

Material: Graffiti, inscribed into marble ledges

Dimensions: (Halfdan) 23cm x 1.5-5 (AribárÞr) 26.8 cm x 3-4.8cm

Dating: 500-1000

Year: IX-XII century

Language: Old Norse

Writing systems: Runic writing